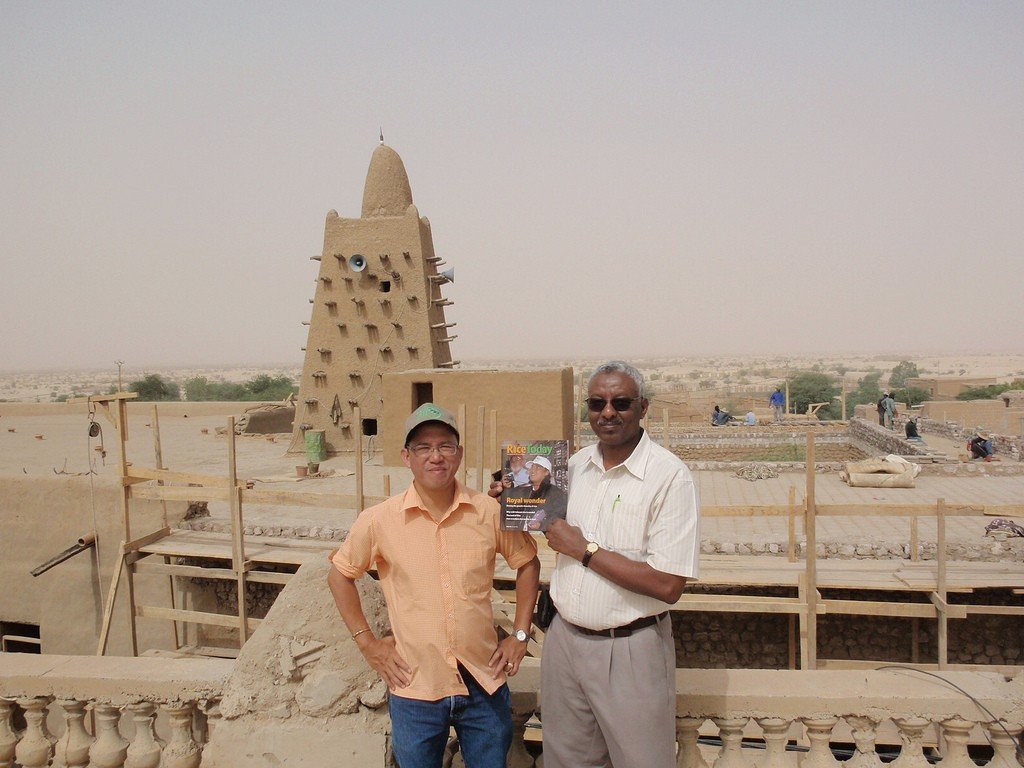

Djingareiber Mosque

Djingareiber Mosque is the central mosque of the city of Timbuktu in Mali. Its bizarre minaret, which from afar looks like a huge anthill or termite, dominates the earthen buildings. Except for a small part of the northern facade, which is made of limestone, the Jingereber Mosque is made of clay with the addition of wood, straw and plant fibers. This structure has three interior rooms, two minarets, and 25 rows of pillars aligned east-west, a prayer hall for 2,000 people.

History

The history of the Jingereber Mosque is linked to a local legend of the Tuareg (a people of the Berber group in Mali).

.Almost a thousand years ago, in one of the bends of the Niger River lived a woman who was characterized by a kind heart and rare hospitality. All caravans traveling across the deserts from the south to the north of the continent would stop at her well to rest. The name of this woman was Buktu, and the word for well in the language of this tribe was Tim. And so it came to pass that time immortalized the memory of the good woman-guardian in the name of the settlement, now a city, Timbuktu.

.

The founders of the city were Tuaregs, and the period of prosperity falls at the beginning of the conquest of the upper Niger River by the Mandigo tribe. Around the legendary well, forming ethnic neighborhoods, Muslim Berbers, Arab traders, and black slaves began to settle. The crossroads of five caravan routes, Timbuktu developed as a trading center. Gold, ivory, crocodile skin, exotic animal furs, kola nuts, slaves, and other goods traveled from the continent northward to the Middle East. From the north, salt, silk and brocade fabrics and other curiosities of oriental luxury were carried through the city. Timbuktu, in the words of the medieval Arab geographer Ibn Khaldun, becomes a “harbor in the desert,” and European traders call it – “the city of gold.”

.In the 12th century, the city becomes part of the then powerful Mali Empire. The ruling Sultan Musa Kankan leads the country to its highest prosperity.

.

While making a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1325, Sultan Musa met the Andalusian architect Abu el-Saheli and for a large reward commissioned the architect to decorate the city of Timbuktu with a delightful palace and mosque. Moreover, the mosque must be not just large, but able to accommodate all the inhabitants of the city.

.

Amazing and the timing of construction: according to the German researcher H. Barth in 1853 over the main entrance to the mosque could see the inscriptions “Kankan Musa” and “1327”. The reason for such a fast, colossal construction (only two years) was the use of traditional building materials – “banco” (a mixture of clay with cut straw) and structures (frames made of poles).

.Jingereber has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1988 as part of Site 119 “Historic City of Tombouctou” together with mosques such as: Sankore and Sidi Yahya.

.In 1990, it was feared by experts that the mosque could be filled with sand. In June 2006, a four-year project to restore the Jinguereber Mosque began.

In 2012, during an armed standoff between the Malian government and Islamist militants, Timbuktu’s mosques were subjected to destruction by the Islamists who had taken over the city. The graves of Muslim saints attached to the mosques were destroyed.

Today, the Jingereber Mosque is the oldest, largest and most famous of Timbuktu’s three mosques. Also unique to this mosque is the fact that not only Muslims can visit it. Visitors are even allowed to climb the minaret for a bird’s eye view of the city. The prayer hall of the mosque is divided into ten aisles by nine rows of square pillars and can accommodate 2,000 people at a time.

.The main enemies of Timbuktu’s clay-built mosques over the centuries have been wind and desert sand. Every two years, or even more often, the fragile clay colossi need to be repaired – the walls and flat roof of the mosque have to be re-clayed. This work is seen by the people of Timbuktu as a religious duty. The city’s masons’ guild is hired for small restoration measures, but in many cases the entire male population of the city comes to work. In recent years, UNESCO and other international organizations have become actively involved in saving Timbuktu’s ancient monuments.

.